Clean patching

When it comes to patching and mocking, Python's built-in libraries are amazing. But if you write a lot of tests you will start to hate patching expressions like this decorator:

@patch("myapp.mycode.imported_name")

or this with statement:

with patch("myapp.mycode.imported_name") as mock_imported_name:

The problems

First of all, they require a lot of typing, and second, they are very fragile.

Typing is prone to typos and copy-paste-errors. And if you refactor your code and move mycode to another module, you will have to change all the patching expressions in your tests. Although powerful IDEs like PyCharm can help you with that to some extent, manually fixing the remaining patch statements is still a pain.

Good news: you can avoid the whole stuff with clean coding and some Python magic. You can take the magic literally as we will use a so-called magic attribute. (an attribute with double underscores at the beginning and the end of their names, like __doc__ or __name__.)

So, if you hate unnecessary typing and wasting time fixing your once well-written code at refactor time, read on.

The solution

You can tackle it from three directions. The first one is trivial. If you test a lot, then you are already using it: mock the method instead of patching it like this:

self.test_object.method = Mock()

Unlike patching, it won't reset the method to the original object later, but that shouldn't be a problem in most cases since you should reset your test object between tests with method-level setups anyway.

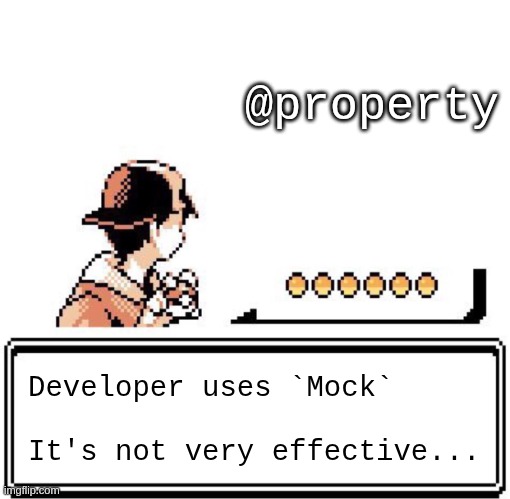

Then there are the properties. We can't use value assignment on them.

But patch.object comes to the rescue. You can call it with the class the property belongs to. Since we're talking about unit tests, the class being tested is already imported to be used in the test setup. This will be the solution:

@patch.object(MyClass, "property_to_mock", new_callable=PropertyMock, return_value="mock_value")

def test_some_method_using_the_property(self, mocked_property: Mock) -> None:

pass

Great! We're fine with methods and properties then. But how to deal with patching imported names? This approach works best for explicit imports, like from json import loads.

class TestMyClass:

namespace = MyClass.__module__

@patch(f"{namespace}.loads") # imported as `from json import loads` in the module

def test_some_method_where_json_loads_is_used(self, mocked_loads: Mock) -> None:

pass

Beautiful, isn't it? The module name is used dynamically, and you can reuse it anywhere. No more novel-length patching expressions that break during refactoring!

Longer self-explanatory code examples you can try out:

src/myapp/mycode.py

from json import loads

class MyCode:

MY_JSON = """{"content": "Hello, World!"}"""

@property

def my_property(self) -> str:

return loads(self.MY_JSON)["content"]

def my_method(self) -> str:

return loads(self.MY_JSON)["content"]

def my_other_method(self) -> str:

return ":)" if self.my_method() == self.my_property else ":("

tests/test_myapp/test_mycode.py

from unittest.mock import Mock, PropertyMock, patch

from myapp.mycode import MyCode

class TestMyCode:

# define this so you don't have hardcode anything when you patch:

namespace = MyCode.__module__

def setup_method(self) -> None:

self.test_object = MyCode()

# Instead of this:

# @patch("myapp.mycode.loads", return_value={"content": "test text"})

# use this:

@patch(f"{namespace}.loads", return_value={"content": "test text"})

def test_my_property(self, mocked_loads: Mock) -> None:

# Act

result = self.test_object.my_property

# Assert

assert result == "test text"

mocked_loads.assert_called_once_with(self.test_object.MY_JSON)

# Instead of this:

# @patch(f"myapp.mycode.MyCode.my_property", new_callable=PropertyMock, return_value="test text")

# use this:

@patch.object(MyCode, "my_property", new_callable=PropertyMock, return_value="test text")

def test_my_other_method(self, mocked_property: Mock) -> None:

# Arrange

# If you reinstantiate the test instance between tests (you should)

# than for method mocking, use Mock directly:

self.test_object.my_method = Mock(return_value="test text")

# Act

result = self.test_object.my_other_method()

# Assert

assert result == ":)"

mocked_property.assert_called_once()

self.test_object.my_method.assert_called_once()

pyproject.toml

[tool.pytest.ini_options]

addopts = "--cov"

pythonpath = ["src"]

testpaths = ["tests"]

[tool.coverage.run]

source = ["src"]

[tool.ruff]

exclude = [".venv"]

lint.ignore = ["E501"]

lint.select = ["E", "F", "W", "C901", "I", "N", "UP", "YTT", "ANN", "SLF", "RET", "TC", "PTH"]

preview = true

target-version = "py313"

requirements.txt

pytest-cov==7.0.0

ruff==0.8.3

My Computer

My Computer

Categories

Categories

Network neighborhood

Network neighborhood

Degoogling

Degoogling

Along the Edge

Along the Edge

My oldest things

My oldest things

My Phones

My Phones

Road 96 - My Journey

Road 96 - My Journey

Custom Font in JetBrains Terminal

Custom Font in JetBrains Terminal

Snowfall

Snowfall

Refactoring: Yeelight GUI

Refactoring: Yeelight GUI

Gaming backlog

Gaming backlog

Company culture

Company culture

KDE Neon

KDE Neon

Blaugust - Summary

Blaugust - Summary

Space Colony

Space Colony

Friendships in my life

Friendships in my life

Jousting in video games

Jousting in video games

Helsinki Biennial

Helsinki Biennial

Data & Encryption

Data & Encryption

Intro through traits

Intro through traits

Hospital visit

Hospital visit

Win 3.1 nostalgia

Win 3.1 nostalgia

Poets of the Fall

Poets of the Fall

Project done!

Project done!

Video games that made me learn

Video games that made me learn

Treasure of the Pirate King

Treasure of the Pirate King

Chimera Squad

Chimera Squad

Family history

Family history

Random facts about me

Random facts about me

Discovering the web-browser module

Discovering the web-browser module